Every once in a while, I turn back to a book that I enjoyed (or didn’t enjoy at all) in my early teenage years, only to find that my experience of the book has completely changed.

So it was with A Room With a View. While I didn’t read the book until I was about 16, I believe I must have first watched the film when I was about 10 (and this is one of those instances where the film is astonishingly loyal to the book).

This was the first film I saw Helena Bonham-Carter in, which has made her subsequent films quite startling.

When I first watched and read A Room with a View, it was in the same sort of way that I generally read classic romances (a dreadful habit I need to get out of): as a character study with a love story in it. I think that A Room with a View can still definitely be read in this way – after all, there are so many interesting characters in this novel.

However, this is the first time I have read the book, and felt something deeper in it – understood a sort of moral standing within it, I mean, which can definitely be applied to one’s own life. In this instance, the novel suggests a way of living that is true to yourself, and true to decency, while disregarding the niceties of society.

The story follows Lucy Honeychurch, a young woman who is travelling in Europe with her poor older cousin, Miss Charlotte Bartlett. The two of them are shocked to meet two men in their Pensione in Florence who not only come from the working class, but also disregard tact – when they mention dissatisfaction with the room they’ve been given, the men (Mr Emerson and his son George), immediately offer them their own room in exchange. Note: this is considered inappropriate because it leaves the two women beholden to strange men.

While they are in Florence, Lucy finds herself in a number of situations which challenge her ideas of how to behave; she is separated from her chaperone while exploring the city, witnesses a murder, and finally finds herself being kissed by George, in a field above Florence. Charlotte convinces her that George views this as an exploit, and they leave.

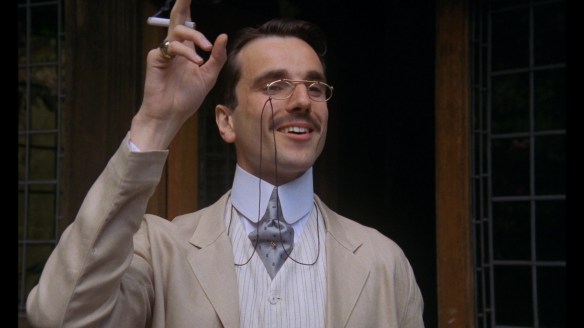

In the second part of the book, Lucy returns home with her new fiance Cecil (in the film, played by Daniel Day-Lewis).

This was also the first film I saw Daniel Day Lewis in – which made all his other film roles even more of a shock than those of Helena Bonham-Carter.

Cecil is a bit of a snob – he looks down on her friends and family as being too middle-class, closed-off, and not interested enough in the higher things of life (such as art and music). He is actually a fascinating character: he doesn’t become a villain at any point, when it would be very easy to make him one. Nor is he particularly ridiculous. His one fault is that he is a restraining influence on Lucy, wanting her to fit into a particular mould, mix with particular people and live in a particular way.

I will leave the ending to you to discover, but I will say that this is a wonderful book, both as a character study of Edwardian society, and as a way of understanding a radical lifestyle lived in an unobtrusive manner. It is well worth reading, and also very short. Also, the film is lovely.

![dapperdan[1]](https://slightlyshortsighted.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/dapperdan1.jpg?w=584)

![banner_the_sirens[1]](https://slightlyshortsighted.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/banner_the_sirens1.jpg?w=300&h=204)

![les-miserables-3877[1]](https://slightlyshortsighted.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/les-miserables-38771.jpg?w=516&h=295)